Specifically, a parent typically holds a direct financial interest in a single subsidiary. This ownership pattern expedites the explanation of consolidation theories and techniques. In practice, though, more elaborate corporate structures commonly exist. General Electric Company (GE), for example, controls literally scores of subsidiaries.

However, GE directly owns voting stock in relatively few of these companies. It maintains control through indirect ownership because GE’s subsidiaries hold the stock of many of the companies within the business combination. For example, GE, the parent company, owns a controlling interest in the voting stock of NBC Universal, Inc., which in turn has total ownership of CNBC and other companies. This type of corporate configuration is referred to as a father-son-grandson relationship because of the pattern the descending tiers create.

Forming a business combination as a series of indirect ownerships is not an unusual practice. Many businesses organize their operations in this manner to group individual companies along product lines, geographic districts, or other logical criteria. The philosophy behind this structuring is that placing direct control in proximity to each subsidiary can develop clearer lines of communication and responsibility reporting.

However, other indirect ownership patterns are simply the result of years of acquisition and growth. As an example, in purchasing General Foods, Philip Morris Companies, Inc. (now Altria Group Inc.), gained control over a number of corporations (including Oscar Mayer Foods Corporation, Maxwell House Coffee Company, and Birds Eye, Inc.). Philip Morris did not achieve this control directly but indirectly through the acquisition of their parent company.

The Consolidation Process when Indirect Control is Present:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Regardless of a company’s reason for establishing indirect control over a subsidiary, a new accounting problem occurs. The parent company must consolidate financial information from several connecting corporations into a single set of financial statements. Fortunately, indirect ownership does not introduce any new conceptual issues but affects only the mechanical elements of this process.

For example, in preparing consolidated statements, the parent company must prepare acquisition-date fair-value allocations and recognize any related excess amortizations for each affiliate regardless of whether control is direct or indirect. In addition, all worksheet entries previously demonstrated continue to apply. For business combinations involving indirect control, the entire consolidation process is basically repeated for each separate acquisition.

Calculation of Subsidiary Income:

Although the presence of an indirect ownership does not change most consolidation procedures, a calculation of each subsidiary’s accrual-based income does pose some difficulty. Appropriate determination of this figure is essential because it serves as the basis for calculating- (1) equity income accruals and (2) the non-controlling interest’s share of consolidated income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

When indirect control is involved, at least one company within the business combination (and possibly many) holds both a parent and a subsidiary position. Any company in that position must first recognize the equity income accruing from its subsidiaries before computing its own income total. This guideline is not a theoretical doctrine but merely a necessary arrangement for calculating income totals in a predetermined order. The process begins with the grandson, then moves to the son, and finishes with the father. Only by following this systematic approach is the correct amount of accrual-based income determined for each individual company.

The respective accrual- based income figures for each affiliate in the consolidated entity therefore must take into account:

i. Excess acquisition-date fair value over book value amortizations.

ii. Deferrals and subsequent income recognition from intercompany transfers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Income Computation Illustrated:

For example, assume that three companies form a business combination: Top Company owns 70 percent of Midway Company, which, in turn, possesses 60 percent of Bottom Company. As the following display indicates, Top controls both subsidiaries, although the parent’s relationship with Bottom is only of an indirect nature.

Assume next that the following information comes from the 2009 individual financial records of the three companies making up this combination:

As specified, we begin with the grandson of the organization and calculate each company’s 2009 accrual-based income. From the perspective of the business combination, Bottom’s income for the period is only $55,000 after deferring the $20,000 in net intercompany gains and recognizing the $25,000 excess amortization associated with the acquisition by Midway. Thus, $55,000 is the basis for the equity accrual by its parent and non-controlling interest recognition.

Once the grandson’s income has been derived, this figure then is used to compute the accrual-based earnings of the son, Midway:

Midway’s $223,000 accrual-based income figure varies significantly from the company’s internally calculated profit of $350,000. This difference is not unusual and merely reflects an appropriate consolidated perspective in viewing the position of the company within the affiliated ownership structure and the consequent effects of excess amortization and intercompany transfers. Continuing with the successive derivation of each company’s earnings, we now can determine Top’s income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

After computing the son’s earnings, the father’s earnings are derived as follows:

We should note several aspects of the accrual-based income data:

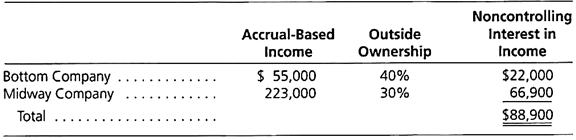

1. The 2009 income statement for Top Company and its consolidated subsidiaries discloses an $88,900 balance as the “non-controlling interests’ share of subsidiary income.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The total accrual-based income figures of the two subsidiaries provide the basis for the calculation as follows:

2. Although this illustration applies the initial value method to both investments, the parent’s individual accounting does not affect accrual-based income totals. The initial value figures are simply replaced with equity accruals in preparation for consolidation. The selection of a particular method is relevant only for internal reporting purposes; earnings, as shown here, are based entirely on the equity income accruing from each subsidiary.

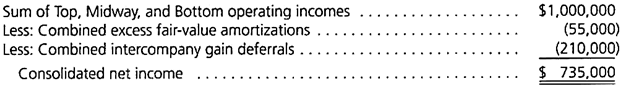

3. If appropriate equity accruals are recognized, the sum of the parent’s accrual-based income and the non-controlling interest income share serves as a “proof figure” for the consolidated total. Thus, if the consolidation process is performed correctly, the earnings this entire organization reports should equal $735,000 ($646,100 + $88,900).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Observe that consolidated net income can also be computed as follows:

4. When indirect control is established, a discrepancy exists between the percentage of stock held and the income contributed to the business combination by a subsidiary. In this illustration, Midway possesses 60 percent of Bottom’s voting stock, but, mathematically, only 42 percent of Bottom’s income is attributed to Top’s controlling interest (70% direct ownership of Midway × 60% indirect ownership of Bottom). The remaining income earned by this subsidiary is assigned to the owners outside the combination.

The validity of this 42 percent accrual is not readily apparent. Therefore, we construct an elementary example to demonstrate the mathematical accuracy of this percentage. Assume that neither Top nor Midway reports any earnings during the year but that Bottom has $100 in accrual-based income. If Bottom declares a $100 cash dividend, $60 goes to Midway and the remaining $40 goes to Bottom’s non-controlling interest. Assuming then that Midway uses this $60 to pay its own dividend, $42 (70 percent) is transferred .to Top and $18 goes to Midway’s outside owners.

Thus, 58 percent of Bottom’s income should be attributed to parties outside the business combination. An initial 40 percent belongs to Bottom’s own non-controlling interest and an additional 18 percent accrues eventually to Midway’s other shareholders. Consequently, only 42 percent of Bottom’s original income is considered earned by the combination. Consolidated financial statements reflect this allocation by including 100 percent of the subsidiary’s revenues and expenses and simultaneously recognizing a reduction for the 58 percent of the subsidiary’s net income attributable to the non-controlling interest.

Consolidation Process—Indirect Control:

After analyzing the income calculations within a father-son-grandson configuration, a full- scale consolidation can be produced. As demonstrated, this type of ownership pattern does not alter significantly the worksheet process. Most worksheet entries are simply made twice first for the son’s investment in the grandson and then for the father’s ownership of the son.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Although this sudden doubling of entries may seem overwhelming, close examination reveals that the individual procedures remain unaffected.

To illustrate, assume that on January 1, 2009, Big acquires 80 percent of Middle’s outstanding common stock for $640,000. On that date, Middle has a book value (total stockholders’ equity) of $700,000 and the 20 percent non-controlling interest has a fair value of $160,000. The resulting excess of subsidiary fair value over book value is assigned to franchises and amortized at the rate of $10,000 per year.

Following the acquisition, Middle’s book value rises to $1,080,000 by the end of 2011, denoting a $380,000 increment during this three-year period ($1,080,000 – $700,000). Big applies the partial equity method; therefore, the parent accrues a $304,000 ($380,000 × 80%) increase in the investment account (to $944,000) over this same time span.

On January 1, 2010, Middle acquires 70 percent of little for $462,000. Little’s stockholders’ equity accounts total $630,000 and the fair value of the 30 percent non-controlling interest is $198,000. Middle allocates this entire $30,000 excess fair value to franchises so that, over a 6-year assumed life, the business combination amortization recognizes an expense of $5,000 each year. During 2010 – 2011, Little’s book value increases by $150,000, to a $780,000 total. Because Middle also applies the partial equity method, it adds $105,000 ($150,000 × 70%) to the investment account to arrive at a $567,000 balance ($462,000 4- $105,000).

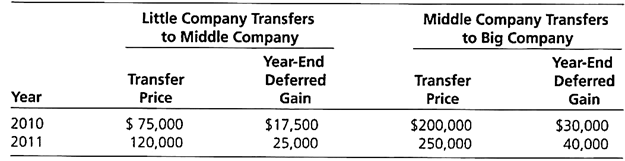

To complete the introductory information for this illustration, assume that a number of intercompany upstream transfers occurred over the past two years.

The following table shows the dollar volume of these transactions and the unrealized gain in each year’s ending inventory:

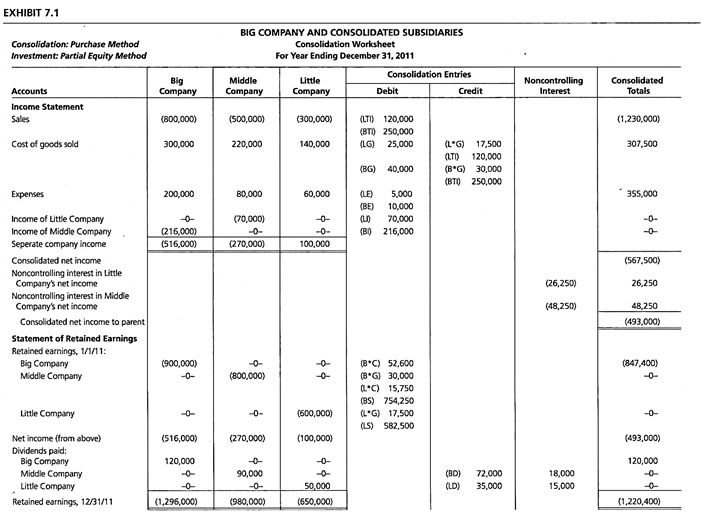

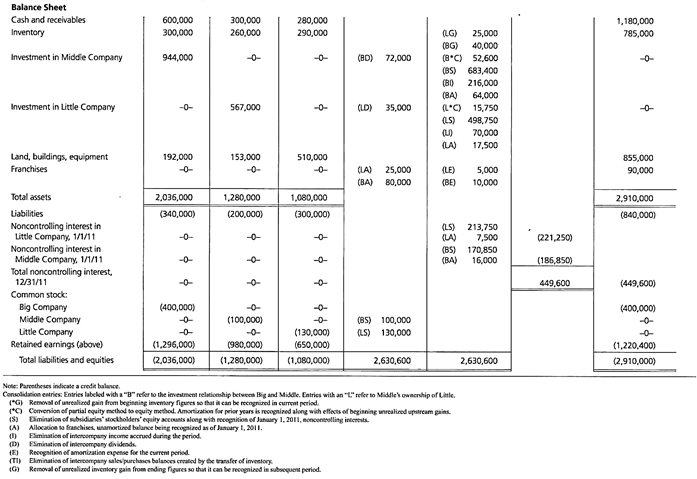

Exhibit 7.1, presents the worksheet to consolidate these three companies for the year ending December 31, 2011. The first three columns represent the individual statements for each organization. The entries required to consolidate the various balances follow this information.

To identify the separate procedures, entries concerning the relationship between Big (father) and Middle (son) are marked with a “B,” whereas an “L” denotes Middle’s ownership of little (grandson). Duplicating entries in this exhibit is designed to facilitate a clearer understanding of this consolidation. A number of these dual entries can be combined later.

To arrive at consolidated figures, Exhibit 7.1 incorporates the worksheet entries described next. Analyzing each of these adjustments and eliminations can identify the consolidation procedures necessitated by a father-son-grandson ownership pattern. Despite the presence of indirect control over little, financial statements are created for the business combination as a whole utilizing the process.

Consolidation Entry *G:

Entry *G defers the intercompany gains contained in the beginning financial figures. Within their separate accounting systems, two of the companies prematurely recorded income ($17,500 by little and $30,000 by Middle) in 2010 at the transfer. For consolidation purposes, a 2010 worksheet entry eliminates these gains from both beginning Retained Earnings as well as Cost of Goods Sold (the present location of the beginning inventory). Consequently, the consolidated income statement recognizes the appropriate gross profit for the current period.

Consolidation Entry *C:

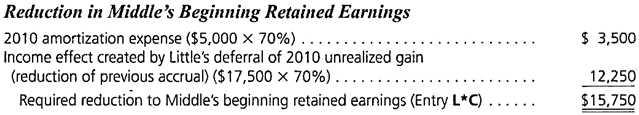

Neither Big nor Middle applies the full equity method to its investments; therefore, the figures recognized during the years prior to the current period (2011) must now be updated on the worksheet. This process begins with the son’s ownership of the grandson. Hence, Middle must reduce its 2010 income (now closed into Retained Earnings) by $3,500 to reflect the amortization applicable to that year. Middle did not record this expense in applying the partial equity method.

In addition, because $17,500 of little’s previously reported earnings have just been deferred (in preceding Entry *G), the effect of this reduction on Middle’s ownership must also be recognized. The parent’s original equity accrual for 2010 is based on reported rather than accrual-based profit thus recording too much income. Little’s deferral necessitates Miller’s parallel $12,250 decrease ($17,500 × 70%).

Consequently, the worksheet reduces Middle’s Retained Earnings balance as of January 1, 2011, and the Investment in Little account by a total of $15,750:

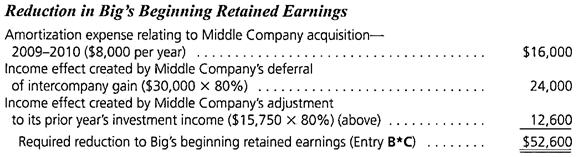

A similar equity adjustment is required in connection with Big’s ownership of Middle. The calculation of the specific amount to be recorded follows the same procedure identified earlier for Middle’s investment in little. Again, amortization expense for all prior years (2009 and 2010, in this case) is brought into the consolidation as well as the income reduction created by the deferral of Middle’s $30,000 unrealized gain (Entry *G).

However, recognition also must be given to the effects associated with the $15,750 decrease in Middle’s pre-2011 earnings. Although recorded only on the worksheet, this adjustment is a change in Middle’s originally reported income. To reflect Big’s ownership of Middle, the effect of this reduction must be included in determining the income balances actually accruing to the parent company.

Thus, a $52,600 decrease is needed in Big’s beginning Retained Earnings to establish the proper accounting for its subsidiaries:

Consolidation Entry S:

The beginning stockholders’ equity accounts of each subsidiary are eliminated here and non-controlling interest balances as of the beginning of the year are recognized. The preliminary adjustments described earlier directly affect the amounts involved in this entry. Because Entry *G removed a $ 17,500 beginning gain, Little’s January 1,2011, book value on the worksheet is $712,500, not $730,000. This total is the basis for recording a $213,750 beginning non-controlling interest (30 percent) and the $498,750 elimination (70 percent) from the parent’s investment account.

Similarly, Entries *G ($30,000) and *C ($15,750) have already decreased Middle’s book value by $45,750. Thus, this company’s beginning stockholders’ equity accounts are now adjusted to a total of $854,250 ($900,000 – $45,750). This balance leads to a $170,850 initial non-controlling interest valuation (20 percent) and a $683,400 (80 percent) offset against Big’s Investment in Middle account.

Consolidation Entry A:

The unamortized franchise balances remaining as of January 1, 2011, are removed from the two investment accounts so that this intangible asset can be identified separately on the consolidated balance sheet. Because Entry *C, already recognizes amortization expense for the previous periods, only beginning totals for the year of $25,000 ($30,000 – $5,000) and $80,000 ($100,000 – $20,000) still remain from the original amounts paid. These totals are allocated across the controlling and non-controlling interests.

Consolidation Entry I:

This entry eliminates the current intercompany income figures accrued by each parent through its application of the partial equity method.

Consolidation Entry D:

Intercompany dividends distributed during the year are removed here from the consolidated financial totals.

Consolidation Entry E:

The annual amortization expense relating to each of the franchise balances is recorded. Consolidation Entry TI.

The intercompany sales/purchases figures created by the transfer of inventory during 2011 are eliminated on the worksheet.

Consolidation Entry G:

This final consolidation entry defers the intercompany inventory gains that remain unearned as of December 31, 2011. The profit on these transfers is removed until the merchandise is subsequently sold to unrelated parties.

Non-Controlling Interests’ Share of Consolidated Income:

To complete the steps that constitute this consolidation worksheet, the 2011 income accruing to owners outside the business combination must be recognized.

This allocation is based on the accrual-based earnings of the two subsidiaries, which is calculated beginning with the grandson (Little) followed by the son (Middle):

Although computation of Big’s earnings is not required here, this figure along with the consolidated income allocations to the non-controlling interests, verifies the accuracy of the worksheet process:

This $493,000 figure represents the income derived by the parent from its own operations plus the earnings accrued from the company’s two subsidiaries (one directly owned and the other indirectly controlled). This balance equals Big Company’s share of the consolidated income of the business combination. As Exhibit 7.1 shows, the income reported by Big Company does, indeed, net to this same total- $493,000.

Indirect Subsidiary Control—Connecting Affiliation:

The father-son-grandson organization is only one of many corporate ownership patterns. The number of possible configurations found in today’s business world is almost limitless. To illustrate the consolidation procedures that accompany these alternative patterns, we briefly discuss a second basic ownership structure referred to as a connecting affiliation.

It exists when two or more companies within a business combination own an interest in another member of that organization.

The simplest form of this configuration is frequently drawn as a triangle:

In this example, both High Company and Side Company maintain an ownership interest in Low Company, thus creating a connecting affiliation. Although neither of these individual companies possesses enough voting stock to establish direct control over Low’s operations, the combination’s members hold a total of 75 percent of the outstanding shares. Consequently, control lies within the single economic entity’s boundaries and requires inclusion of Low’s financial information as a part of consolidated statements.

Consistent with SFAS 141R, on the date the parent obtains control, the valuation basis for the subsidiary in the parent’s consolidated statements is established. For Low, we assume that Side Company’s ownership preceded that of High’s. Subsequently, High obtained control upon acquiring its 30 percent interest in Low and the valuation basis for inclusion of Low’s assets and liabilities (and related excess fair value over book value amortization) was established at that date.

The process for consolidating a connecting affiliation is essentially the same as for a father-son-grandson organization. Perhaps the most noticeable difference is that more than two investments are always present. In this triangular business combination, High owns an interest in both Side and Low while Side also maintains an investment in Low.

Thus, unless combined in some manner, three separate sets of consolidation entries appear on the worksheet. Although the added number of entries certainly provides a degree of mechanical complication, the basic concepts involved in the consolidation process remain the same regardless of the number of investments.

As with the father-son-grandson structure, one key aspect of the consolidation process warrants additional illustration- the determination of accrual-based income figures for each individual company. Therefore, assume that High, Side, and Low have separate internally calculated operating incomes (without inclusion of any earnings from their subsidiaries) of $300,000, $200,000, and $100,000, respectively. Each company also retains a $30,000 net intercompany gain in its current year income figures. Assume that annual amortization expense of $10,000 has been identified within the acquisition-date excess fair value over book value for each of the two subsidiaries.

In the same manner as a father-son-grandson organization, determining accrual-based earnings begins with any companies solely in a subsidiary position (Low, in this case). Next companies that are both parents and subsidiaries (Side) compute their accrual- based income. Finally, this same calculation is made for the one company (High) that has ultimate control over the entire combination.

Accrual-based income figures for the three companies in this combination are derived as follows:

Low Company’s Accrual-Based Income and Non-Controlling Interest:

Side Company’s Accrual-Based Income and Non-Controlling Interest:

High Company’s Accrual-Based Income:

Although in this illustration a connecting affiliation exists, the basic tenets of the consolidation process remain the same:

i. Removed all effects from intercompany transfers.

ii. Adjust the parents’ beginning Retained Earnings to recognize the equity income resulting from ownership of the subsidiaries in prior years. Determining accrual-based earnings for this period properly aligns the balances with the perspective of a single economic entity.

iii. Eliminate the beginning stockholders’ equity accounts of each subsidiary and recognize the non-controlling interests’ figures as of the first day of the year.

iv. Enter all unamortized balances created by the original acquisition-date excess of fair value over book value onto the worksheet and allocated to controlling and non-controlling interests.

v. Recognize amortization expense for the current year.

vi. Removed intercompany income and dividends.

vii. Compute the non-controlling interests’ share of the subsidiaries’ net income and include it in the business combination’s financial statements.