Compilation of advanced accounting final exam questions and answers for students.

Q.1. What Problems does Accounting Diversity Cause?

Ans. The diversity in accounting practices across countries causes problems that can be quite serious for some parties. One problem relates to the preparation of consolidated financial statements by companies with foreign operations. Consider The Coca-Cola Company, which has subsidiaries in more than 100 countries around the world. Each subsidiary incorporated in the country in which it is located is required to prepare financial statements in accordance with local regulations.

These regulations usually require companies to keep books in the local currency and follow local accounting principles. Thus, Coca-Cola Italia SRL prepares financial statements in euros using Italian accounting rules, and Coca-Cola Amatil Ltd., prepares financial statements in Australian dollars using Australian standards. To prepare consolidated financial statements in the United States, in addition to translating the foreign currency financial statements into U.S. dollars, the parent company must also convert the financial statements of its foreign subsidiaries into U.S. GAAP.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Each foreign subsidiary must either maintain two sets of books prepared in accordance with both local and U.S. GAAP or, as is more common, make reconciliations from local GAAP to U.S. GAAP at the balance sheet date. In either case, considerable effort and cost are involved; company personnel must develop an expertise in more than one country’s accounting standards.

A second problem relates to companies gaining access to foreign capital markets. If a company desires to obtain capital by selling stock or borrowing money in a foreign country, it might be required to present a set of financial statements prepared in accordance with the accounting standards in the country in which the capital is being obtained. Consider the case of the Swedish appliance manufacturer Electrolux.

The equity market in Sweden is so small (there are fewer than 9 million Swedes) and Electrolux’s capital needs are so great that the company found it necessary to have its common shares listed on foreign stock exchanges in London and Frankfurt and on NASDAQ in the United States.

To have their stock traded in the United States, foreign companies must reconcile financial statements to U.S. accounting standards. This can be quite costly. To prepare for a New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) listing in 1993, the German automaker Daimler-Benz estimated it spent $60 million to initially prepare U.S. GAAP financial statements; it planned to spend $15 million to 20 million each year thereafter.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A third problem relates to the lack of comparability of financial statements between companies from different countries. This can significantly affect the analysis of foreign financial statements for making investment and lending decisions. In 2005 alone, U.S. investors bought nearly $180 billion in debt and equity of foreign entities while foreign investors pumped approximately $474 billion into U.S. entities through similar acquisitions.

In the 1990s, there was an explosion in mutual funds that invest in the stock of foreign companies—from 123 in 1989 to 1,621 at the end of 1999. T. Rowe Price’s New Asia Fund, for example, invests exclusively in stocks and bonds of companies located in Asian countries other than Japan.

The job of deciding which foreign company to invest in is complicated by the fact that foreign companies use accounting rules that differ from those used in the United States, and those rules differ from country to country. It is very difficult, if not impossible, for a potential investor to directly compare the financial position and performance of chemical companies in Germany (BASF), China (Sinopec), and the US. (DuPont) because these three countries have different financial accounting and reporting standards.

A lack of comparability of financial statements also can have an adverse effect on corporations when making foreign acquisition decisions. As a case in point, consider the experience of foreign investors in Eastern Europe. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, officials invited Western companies to acquire newly privatized companies in Poland, Hungary, and other countries in the former communist bloc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The concept of profit and accounting for assets in those countries under communism was so much different from accounting practice in the West that most Western investors found financial statements useless in helping them determine the most attractive acquisition targets. Many investors asked the then Big 5 public accounting firms to convert financial statements to a Western basis before acquisition of a company could be seriously considered.

Q.2. What are the Reasons for Accounting Diversity?

Ans. Why do differences in financial reporting practices across countries exist? Accounting scholars have hypothesized numerous influences on a country’s accounting system, including factors as varied as the nature of the political system, the stage of economic development, and the state of accounting education and research.

A survey of the relevant literature identified the following five items as commonly accepted factors influencing a country’s financial reporting practices:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(1) Legal system,

(2) Taxation,

(3) Providers of financing,

(4) Inflation, and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(5) Political and economic ties.

In addition, many believe that national culture has played an important role in shaping the nature of a country’s accounting system.

The two major types of legal systems used around the world are common law and codified Roman law. Common law began in England and is found primarily in the English-speaking countries of the world. Common law countries rely on a limited amount of statute law interpreted by the courts. Court decisions establish precedents, thereby developing case law that supplements the statutes.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A system of code law, followed in most non-English-speaking countries, originated in the Roman jus civile and was developed further in European universities during the middle Ages. Code law countries tend to have relatively more statute or codified law governing a wider range of human activity.

What does a country’s legal system have to do with accounting? Code law countries generally have a corporation law (sometimes called a commercial code or companies act) that establishes the basic legal parameters governing business enterprises. Corporation law often stipulates which financial statements must be published in accordance with a prescribed format. Additional accounting measurement and disclosure rules are included in an accounting law that has been debated and passed by the national legislature.

The accounting profession tends to have little influence on the development of accounting standards. In countries with a tradition of common law, although a corporation law laying the basic framework for accounting might exist (such as in the United Kingdom), the profession or an independent, nongovernmental body representing a variety of constituencies establishes specific accounting rules. Thus, the type of legal system in a country determines whether the primary source of accounting rules is the government or the accounting profession.

In code law countries, the accounting law is rather general; it does not provide much detail regarding specific accounting practices and may provide no guidance at all in certain areas. Germany is a good example of a code law country. Its accounting law passed in 1985 is only 47 pages long and is silent with regard to issues such as leases, foreign currency translation, and a cash flows statement. In those situations for which the law provides no guidance, German companies must refer to other sources, including tax law and opinions of the German auditing profession, to decide how to do their accounting.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Common law countries, where a nongovernment organization is likely to develop accounting standards, have much more detailed rules. The extreme case might be the FASB in the United States. It provides very specific detail in its Statements of Financial Accounting Standards about how to apply the rules and has been accused of producing a standards overload.

In some countries, published financial statements form the basis for taxation; in other countries, financial statements are adjusted for tax purposes and submitted to the government separately from the reports sent to stockholders. Continuing to focus on Germany, its so-called conformity principle (Massgeblichkeitsprinzip) requires that, in most cases, an expense also must be used in calculating financial statement income to be deductible for tax purposes.

Well-managed German companies attempt to minimize income for tax purposes, for example, by using accelerated depreciation to reduce their tax liability. As a result of the conformity principle, accelerated depreciation also must be taken in calculating accounting income.

In the United States, on the other hand, conformity between the tax statement and financial statements is required only for the use of the LIFO inventory cost-flow assumption. U.S. companies are allowed to use accelerated depreciation for tax purposes and straight-line depreciation in the financial statements. All else being equal, a U.S. company is likely to report higher income than its German counterpart.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The major providers of financing for business enterprises are family members, banks, governments, and shareholders. Those countries in which families, banks, or the state dominate company financing have less pressure for public accountability and information disclosure. Banks and the state often are represented on the board of directors and therefore are able to obtain information necessary for decision making from inside the company.

As companies depend more on financing from the general populace through the public offering of shares of stock, the demand for more information made available outside the company increases. It simply is not feasible for the company to allow the hundreds, thousands, or hundreds of thousands of shareholders access to internal accounting records. The information needs of those financial statement users can be satisfied only by extensive disclosures in accounting reports.

There also can be a difference in orientation, with stockholders more interested in profit (emphasis on the income statement) and banks more interested in solvency and liquidity (emphasis on the balance sheet). Bankers prefer companies to practice rather conservative accounting with regard to assets and liabilities.

Countries with chronically high rates of inflation have been forced to adopt accounting rules that require the inflation adjustment of historical cost amounts. This has been especially true in Latin America, which as a region has had more inflation than any other part of the world. For example, prior to economic reform in the mid-1990s, Brazil regularly experienced annual inflation rates exceeding 100 percent.

The high point was reached in 1993 when annual inflation was nearly 1,800 percent. Double- and triple-digit inflation rates render historical costs meaningless. This factor primarily distinguishes accounting in Latin America from the rest of the world.

(5) Political and Economic Ties:

Accounting is a technology that can be borrowed relatively easily from or imposed on another country. Through political and economic linkages, accounting rules have been conveyed from one country to another. For example, through previous colonialism, both England and France have transferred their accounting frameworks to a variety of countries around the world.

British accounting systems can be found in countries as far-flung as Australia and Zimbabwe. French accounting is prevalent in the former French colonies of western Africa. More recently, economic ties with the United States have had an impact on accounting in Canada, Mexico, and Israel.

Culture:

From a worldwide survey of IBM Corporation employees, Hofstede identified four societal values that can be used to describe similarities and differences in national cultures:

(1) Individualism,

(2) Uncertainty avoidance,

(3) Power distance, and

(4) Masculinity.

Gray developed a model of the development of accounting systems internationally, an adaptation of which is depicted in Exhibit 11.5. In this model, Gray suggested that societal values influence a country’s accounting system in two ways. First, they help shape a country’s institutions, such as its legal system and capital market (providers of financing), which in turn affect the development of the accounting system. Second, societal values influence the accounting values shared by members of the accounting subculture, which in turn influences the nature of the accounting system.

Focusing on the links between culture, accounting values, and accounting systems, Gray developed a number of specific hypotheses. For example, he hypothesized that in a society with a low tolerance for uncertainty (high uncertainty avoidance), accountants prefer more conservative measures of profits and assets (high conservatism). This manifests itself in the accounting system through accounting measurement rules that emphasize the accounting value of conservatism.

As another example, Gray hypothesized that countries in which hierarchy and unequal distribution of power in organizations is readily accepted (high power distance), the preference is for secrecy (high secrecy) to preserve power inequalities. This results in an accounting system in which financial statements disclose a minimal amount of information. Several research studies have found support for a number of Gray’s hypotheses.

Q.2. Explain Solid Waste Landfill.

Ans. The following information is disclosed in the notes to the financial statements of the City of Greensboro, North Carolina, as of June 30, 2006:

The City owns and operates a regional landfill site located in the northeast portion of the City. State and federal laws require the City to place a final cover on its White Street landfill site and to perform certain maintenance and monitoring functions at the site for thirty years after closure.

The City reports a portion of these closure and post-closure care costs as an operating expense in each period based on landfill capacity used as of each June 30. The $12,364,968 reported as landfill closure and post-closure care liability at June 30, 2006, is based on the use of 100% of the estimated capacity of Phase II and Phase III, Cells 1 and 2. Phase III, Cell 3, is estimated at 34.6% filled.

The estimated liability amounts are based on what it would cost to perform all closure and post- closure care in the current year. Actual cost may be higher due to inflation, changes in technology, or changes in regulations. At June 30, 2006, the City had expended $3,876,035 to complete closure for the White Street facility, Phase II. The balance of closure costs, estimated at $6,971,195, and estimated at $5,393,773 for post-closure care will be funded over the remaining life of the landfill.

Thousands of state and local governments operate solid waste landfills to provide a place for citizens and local companies to dispose of trash and other forms of garbage and refuse. Governments frequently report landfill operations within the enterprise funds because many of these facilities require a user fee. However, some landfills are open to the public without fee so that reporting within the General Fund is appropriate.

Regardless of the type of fund utilized, solid waste landfills can be sources of huge liabilities for governments. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has strict rules on closure requirements as well as groundwater monitoring and other post-closure activities. Satisfying such requirements can be quite costly.

Thus, the operation of a landfill eventually necessitates large payments to ensure that the facility is properly closed and then monitored and maintained for an extended period. Theoretically, the relevant accounting question has always been how to report the eventual closure costs while the landfill is still in operation.

To illustrate, assume that a city opens a landfill in Year 1 that is expected to take 10 years to fill. As part of the recording process each year, the city must estimate the current costs required to close the landfill. Such costs include the amount to be paid to cover the area and for all post-closure maintenance. The city uses current rather than future costs as a better measure of the present obligation. However, such amounts must then be adjusted each period for inflation as well as technology and regulation changes.

Assume, for this example, that the current cost for closure is estimated at $1 million and for post-closure maintenance at $400,000. Assume that during Year 1, the city makes an initial payment of $30,000 toward the closure costs. At the end of this first year, city engineers estimate that 16 percent of the space has been filled.

Government-Wide Financial Statements:

Regardless of whether the city reports this solid waste landfill as a governmental activity (within the General Fund) or as a business-type activity (within an enterprise fund), it must recognize the closure and post-closure costs in the government-wide statements based on accrual accounting and the economic resources measurement basis.

Because the government anticipates total costs of $1.4 million and the landfill is 16 percent filled, $224,000 should be accrued in this first year ($1.4 million × 16%):

To extend this example, assume that the landfill is judged to be 27 percent filled at the end of Year 2 and the city makes another $30,000 payment. However, because of inflation and newly anticipated changes in technology, the city now believes that current closure costs would total $1.1 million with post-closure costs amounting to $500,000.

Using this new and revised information, the city should recognize that it has estimated total costs of $432,000 by the end of Year 2 ($1.6 million × 27%).

Because it already recorded $224,000 in Year 1, it now accrues an additional $208,000 in Year 2 ($432,000 – $224,000):

Government-Wide Financial Statements- Year 2:

Fund-Based Financial Statements:

If the city is recording a solid waste landfill as an enterprise fund, the reporting is the same in the fund-based financial statements as just shown. All economic resources are again being measured based on accrual accounting.

However, if the landfill is recorded in the General Fund, the city reports only the change in current financial resources. Despite the huge eventual liability, the reduction in current financial resources is limited to the annual payment of $30,000.

Thus, the only entry required each year in this example for the fund-based financial statements is as follows:

Fund-Based Financial Statements- Year 1 and Year 2:

Q.3. Explain the Pooling of Interests Controversy.

Ans. Over the years, the legitimacy of the pooling of interests method was frequently questioned. One major theoretical problem associated with the pooling method was that it ignored exchange values in the combination. What was normally a significant event for both companies was simply omitted from any accounting consideration.

The pooling of interests method was very popular in the business world largely based on the desirable impact that it usually produced on reported net income. The most obvious effect was the inclusion of the subsidiary’s net income as if that company had always been part of the consolidated entity. This retrospective treatment led to immediate improvement in the combined firm’s profitability picture.

Another income effect helped to further account for the popularity enjoyed by the pooling of interests method. In a purchase combination, the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities were adjusted to fair value with goodwill often recognized. During the time that poolings were allowed, all such allocations (except land) required amortization over future accounting periods. The resulting expense, encountered only in the purchase method, served to reduce consolidated net income year after year.

Conversely, a pooling of interests consolidated all accounts at their book values so that no additional amortization expense was ever recognized. Therefore, in most past business combinations, the income reported for each succeeding year was higher using the pooling method than would have been the case if consolidated by the purchase method.

Moreover, financial ratios such as Net Income/Total Assets were often dramatically inflated by the pooling of interests method. To the extent that managerial compensation contracts were based on such accounting measures of profitability, a further motivation to employ the pooling of interests method to accounting for a business combination was provided.

Given these reporting advantages, the desire by businesses to create combinations that would qualify as poolings was not surprising. Historically, the accounting profession attempted to define the characteristics of a pooling of interests in such a way as to restrict its use to combinations that were clearly fusions of two independent companies. Over the years, however, the identification of attributes considered to be essential to a pooling of interests proved to be a difficult task.

In an article supporting their unanimous decision to eliminate the pooling of interests method of accounting for business combinations, the FASB cited the following reasons for their action:

i. The pooling method provides investors with less information—and less relevant information— than that provided by the purchase method.

ii. The pooling method ignores the values exchanged in a business combination while the purchase method reflects them.

iii. Under the pooling method, financial statement readers cannot tell how much was invested in the transaction, nor can they track the subsequent performance of the investment.

iv. Having two methods of accounting makes it difficult for investors to compare companies when they have used different methods to account for their business combinations.

v. Because future cash flows are the same whether the pooling or purchase method is used, the boost in earnings under the pooling method reflects artificial accounting differences rather than real economic differences.

Business combinations are acquisitions and should be accounted for as such, based on the value of what is given up in exchange, regardless of whether it is cash, other assets, debt, or equity shares.

Q.4. What is Foreign Currency Borrowing?

Ans. In addition to the receivables and payables that arise from import and export activities, companies often must account for foreign currency borrowings, another type of foreign currency transaction. Companies borrow foreign currency from foreign lenders either to finance foreign operations or perhaps to take advantage of more favorable interest rates. The facts that both the principal and interest are denominated in foreign currency and both create an exposure to foreign exchange risk complicate accounting for a foreign currency borrowing.

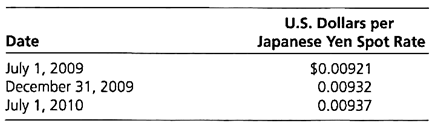

To demonstrate the accounting for foreign currency debt, assume that on July 1, 2009, Multicorp International borrowed 1 billion Japanese yen (¥) on a one-year note at a per annum interest rate of 5 percent. Interest is payable and the note comes due on July 1, 2010.

The following exchange rates apply:

On July 1, 2009, Multicorp borrows ¥ 1 billion and converts it into $9,210,000 in the spot market. On December 31, 2009, Multicorp must revalue the Japanese yen note payable with an offsetting foreign exchange gain or loss reported in income and must accrue interest expense and interest payable. Interest is calculated by multiplying the loan principal in yen by the relevant interest rate.

The amount of interest payable in yen is then translated to U.S. dollars at the spot rate to record the accrual journal entry. On July 1, 2010, any difference between the amount of interest accrued at year- end and the actual U.S. dollar amount that must be spent to pay the accrued interest is recognized as a foreign exchange gain or loss.

These journal entries account for this foreign currency borrowing:

Q.5. What is Foreign Currency Loan?

Ans. At times companies lend foreign currency to related parties, creating the opposite situation from a foreign currency borrowing. The accounting involves keeping track of a note receivable and interest receivable, both of which are denominated in foreign currency. Fluctuations in the U.S. dollar value of the principal and interest generally give rise to foreign exchange gains and losses that would be included in income.

Under SFAS 52, an exception arises when the foreign currency loan is made on a long-term basis to a foreign branch, subsidiary, or equity method affiliate. Foreign exchange gains and losses on “intercompany foreign currency transactions that are of a long-term investment nature (that is, settlement is not planned or anticipated in the foreseeable future)” are deferred in other comprehensive income until the loan is repaid. Only the foreign exchange gains and losses related to the interest receivable are recorded currently in net income.

Q.6. Explain the Translation Methods of Financial Statements.

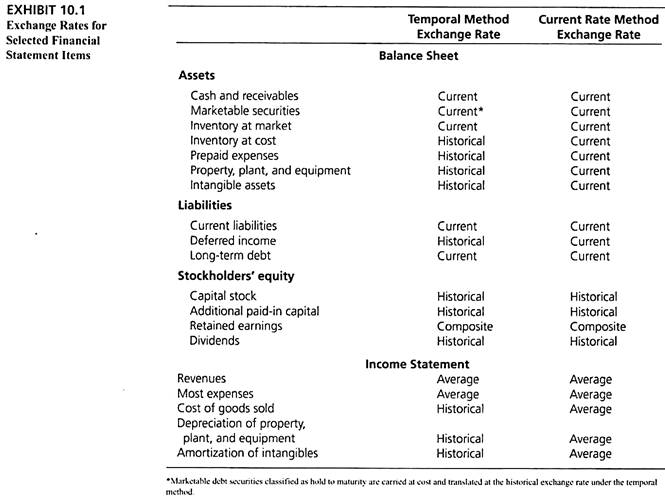

Ans. Two major translation methods are currently used:

(1) Current rate method, and

(2) Temporal method.

We discuss each method from the perspective of a U.S.-based multinational company translating foreign currency financial statements into U.S. dollars.

(1) Current Rate Method:

The basic assumption underlying the current rate method is that a company’s net investment in a foreign operation is exposed to foreign exchange risk. In other words, a foreign operation represents a foreign currency net asset and if the foreign currency decreases in value against the U.S. dollar, a decrease in the U.S. dollar value of the foreign currency net asset occurs.

This decrease in U.S. dollar value of the net investment will be reflected by reporting a negative (debit balance) translation adjustment in the consolidated financial statements. If the foreign currency increases in value, an increase in the U.S. dollar value of the net asset occurs and will be reflected through a positive (credit balance) translation adjustment.

To measure the net investment’s exposure to foreign exchange risk, all assets and all liabilities of the foreign operation are translated at the current exchange rate. Stockholders’ equity items are translated at historical rates. The balance sheet exposure under the current rate method is equal to the foreign operation s net asset (total assets minus total liabilities) position.

Total assets > Total liabilities → Net asset exposure

A positive translation adjustment arises when the foreign currency appreciates, and a negative translation adjustment arises when the foreign currency depreciates.

As mentioned, the major difference between the translation adjustment and a foreign exchange gain or loss is that the translation adjustment is not necessarily realized through inflows and outflows of cash. The translation adjustment arises when using the current rate method is unrealized. It can become a realized gain or loss only if the foreign operation is sold (for its book value) and the foreign currency proceeds from the sale are converted into U.S. dollars.

The current rate method requires translation of all income statement items at the exchange rate in effect at the date of accounting recognition. In most cases, an assumption can be made that the revenue or expense is incurred evenly throughout the accounting period and a weighted average-for-the-period exchange rate can be used for translation. However, when an income account, such as a gain or loss, occurs at a specific point in time, the exchange rate at that date should be used for translation.

(2) Temporal Method:

The basic objective underlying the temporal method of translation is to produce a set of U.S. dollar-translated financial statements as if the foreign subsidiary had actually used U.S. dollars in conducting its operations. Continuing with the Gualos subsidiary example. Southwestern, the U.S. parent, should report the Land account on the consolidated balance sheet at the amount of U.S. dollars that it would have spent if it had sent dollars to the subsidiary to purchase land.

Because the land cost 150,000 vilseks at a time when one vilsek could be acquired with $0.20, the parent would have sent $30,000 to the subsidiary to acquire the land; this is the land’s historical cost in U.S. dollar terms.

The following rule is consistent with the temporal method’s underlying objective:

1. Assets and liabilities carried on the foreign operation’s balance sheet at historical cost are translated at historical exchange rates to yield an equivalent historical cost in U.S. dollars.

2. Conversely, assets and liabilities carried at a current or future value are translated at the current exchange rate to yield an equivalent current value in U.S. dollars.

Application of this rule maintains the underlying valuation method (current value or historical cost) that the foreign subsidiary uses in accounting for its assets and liabilities. In addition, stockholders’ equity accounts are translated at historical exchange rates.

Cash, marketable securities, receivables, and most liabilities are carried at current or future value and translated at the current exchange rate under the temporal method. The temporal method generates either a net asset or a net liability balance sheet exposure, depending on whether cash plus marketable securities plus receivables are more than or less than liabilities.

Cash + Marketable securities + Receivables > Liabilities → Net asset exposure

Cash + Marketable securities + Receivables < Liabilities → Net liability exposure

Because liabilities (current plus long term) usually are more than assets translated at the current exchange rate, a net liability exposure generally exists when the temporal method is used.

One way to understand the concept of exposure underlying the temporal method is to pretend that the parent actually carries on its balance sheet the foreign operation’s cash, marketable securities, receivables, and payables. For example, consider the Japanese subsidiary of a U.S. parent company. The Japanese subsidiary’s yen receivables that result from sales in Japan may be thought of as Japanese yen receivables of the U.S. parent that result from export sales to Japan.

If the U.S. parent had yen receivables on its balance sheet, a decrease in the yen’s value would result in a foreign exchange loss. A foreign exchange loss also occurs on the Japanese yen held in cash by the U.S. parent and on the Japanese yen denominated marketable securities. A foreign exchange gain on the parent’s Japanese yen payables resulting from foreign purchases would offset these foreign exchange losses.

Whether a net gain or a net loss exists depends on the relative amount of yen cash, marketable securities, and receivables versus yen payables. Under the temporal method the translation adjustment measures the “net foreign exchange gain or loss” on the foreign operation’s cash, marketable securities, receivables, and payables, as if those items were actually carried on the parent’s books.

Again, the major difference between the translation adjustment resulting from the use of the temporal method and a foreign exchange gain or loss is that the translation adjustment is not necessarily realized through inflows or outflows of cash. The U.S. dollar translation adjustment in this case is realized only if- (1) the parent sends U.S. dollars to the Japanese subsidiary to pay all of its yen liabilities and (2) the subsidiary converts its yen receivables and marketable securities into yen cash and then sends this amount plus the amount in its yen cash account to the U.S. parent which converts it into U.S. dollars.

The temporal method translates income statement items at exchange rates that exist when the revenue is generated or the expense is incurred. For most items, an assumption can be made that the revenue or expense is incurred evenly throughout the accounting period and an average-for-the-period exchange rate can be used for translation.

However, some expenses are related to assets carried at historical cost—for example, cost of goods sold, depreciation of fixed assets, and amortization of intangibles. Because the related assets are translated at historical exchange rates, these expenses must be translated at historical rates as well.

The current rate method and temporal method are the two methods currently used in the United States. They are also the predominant methods used worldwide. A summary of the appropriate exchange rate for selected financial statement items under these two methods is presented in Exhibit 10.1.

Q.7. How is the Translation of Retained Earnings done?

Ans. Stockholders’ equity items are translated at historical exchange rates under both the temporal and current rate methods. This creates somewhat of a problem in translating retained earnings. This figure is actually a composite of many previous transactions: all revenues, expenses, gains, losses, and declared dividends occurring over the company’s life.

At the end of the first year of operations, foreign currency (FC) retained earnings (RE) is translated as follows:

The same approach translates retained earnings under both the current rate and the temporal methods. The only difference is that translation of the current period net income is calculated differently under the two methods.

Q.8. What are Compensated Absences?

Ans. State and local governments have numerous employees- police officers, schoolteachers, maintenance workers, and the like. As of June 30, 2006, the City of Baltimore, Maryland, reported having 16,239 employees. In the same manner as the employees of a for-profit organization, government employees earn vacation days, sick leave days, and holidays, collectively known as compensated absences that can amount to a significant amount of money. For example, at June 30, 2006, the City of Baltimore reported a debt of more than $106 million for such compensated absences.

This obligation was explained in part through footnote disclosure- “Employees earn one day of sick leave for each completed month of service, and there is no limitation on the number of sick days that can accumulate.”

Accounting for such liabilities is much the same as was demonstrated for capital leases and solid waste landfills. In the government-wide financial statements, the city accrues the expense as incurred. Conversely in producing a fund-based financial statement for the governmental funds, only actual payments and claims to current financial resources are included.

For example, assume that a city reaches the end of Year 1 and owes its General Fund employees $40,000 because of compensated absences to be taken in the future for vacation days, holidays, and sick leave that have been earned. However, only $5,000 of these absences are expected to be taken early enough in Year 2 to require current financial resources. Perhaps several employees are scheduled to take their vacations in the first two months of the subsequent period.

Consequently, a $40,000 liability exists at the end of Year 1 but only $5,000 of that amount is a claim on the government’s current financial resources:

Government-Wide Financial Statements- Year 1:

Reporting for the governmental funds in the fund-based financial statements reflects the changes in current financial resources. As the following entry shows, only the $5,000 that will be paid early in the next year is included. The remainder of the debt is not yet reported because it is not a claim to current financial resources. Again, however, if the employees work in an area of the government reported as an enterprise fund, the fund-based accounting is the same as in the government-wide statements.

Fund-Based Financial Statements: Year 1:

Q.9. Why is Foreign Currency Option used to Hedge a Foreign Currency Denominated Asset?

Ans. As an alternative to a forward contract, Amerco could hedge its exposure to foreign exchange risk arising from the euro account receivable by purchasing a foreign currency put option. A put option would give Amerco the right but not the obligation to sell 1 million euros on March 1, 2010, at a predetermined strike price. Assume that on December 1, 2009, Amerco purchases an over-the-counter option from its bank with a strike price of $ 1.32 when the spot rate is $1.32 and pays a premium of $0,009 per euro. Thus, the purchase price for the option is $9,000 (€1 million × $0,009).

Because the strike price and spot rate are the same, no intrinsic value is associated with this option. The premium is based solely on time value; that is, it is possible that the euro will depreciate and the spot rate on March 1, 2010, will be less than $1.32, in which case the option will be “in the money.” If the spot rate for euros on March 1, 2010, is less than the strike price of $1.32, Amerco will exercise its option and sell its 1 million euros at the strike price of $1.32.

If the spot rate for euros in three months is more than the strike price of $1.32, Amerco will not exercise its option but will sell euros at the higher spot rate. By purchasing this option, Amerco is guaranteed a minimum cash flow from the export sale of $1,311,000 ($1,320,000 from exercising the option less the $9,000 cost of the option). There is no limit to the maximum number of U.S. dollars that Amerco could receive.

As is true for other derivative financial instruments, SFAS 133 requires foreign currency options to be reported on the balance sheet at fair value. The fair value of a foreign currency option at the balance sheet date is determined by reference to the premium quoted by banks on that date for an option with a similar expiration date. Banks (and other sellers of options) determine the current premium by incorporating relevant variables at the balance sheet date into the modified Black-Scholes option pricing model.

Changes in value for the euro account receivable and the foreign currency option are summarized as follows:

Because the option strike price is less than or equal to the spot rate at both December 1 and December 31, the option has no intrinsic value at those dates. The entire fair value is attributable to time value only. On March 1, the date of expiration, no time value remains, and the entire amount of fair value is attributable to intrinsic value.

Option Designated as Fair Value Hedge:

Assume that Amerco decides not to designate the foreign currency option as a cash flow hedge but to treat it as a fair value hedge. In that case, it takes the gain or loss on the option directly to net income and does not separately recognize the change in the time value of the option.

The Impact or net income for the year 2010 follows:

Over the two accounting periods, Amerco reports Sales of $1,320,000 and a cumulative net loss of $9,000 ($7,000 net gain in 2009 and $16,000 net loss in 2010). The net effect on the balance sheet is an increase in Cash of $1,311,000 ($1,320,000 – $9,000) with a corresponding increase in Retained Earnings of $1,311,000 ($1,327,000 – $16,000). The net benefit from having acquired the option is $11,000. Amerco reflects this in net income through the net Gain on Foreign Currency Option ($3,000 loss in 2009 and $14,000 gain in 2010) recognized over the two accounting periods.

The accounting for an option used as a fair value hedge of a foreign currency denominated asset or liability is the same as if the option had been considered a speculative derivative. The only advantage to designating the option as a fair value hedge relates to the disclosures made in the notes to the financial statements.

Spot Rate Exceeds Strike Price:

If the spot rate at March 1, 2010, had been more than the strike price of $1.32, Amerco would allow its option to expire unexercised. Instead it would sell its foreign currency (€) at the spot rate. The fair value of the foreign currency option on March 1, 2010, would be zero. The journal entries for 2009 to reflect this scenario would be the same as the preceding ones. The option would be reported as an asset on the December 31, 2009, balance sheet at $6,000 and the € receivable would have a carrying value of $1,330,000.

The entries on March 1, 2010, assuming a spot rate on that date of $1,325 (rather than $1.30), would be as follows: