After reading this article you will learn about:- 1. Meaning of Cost Benefit Analysis 2. Fundamentals of Cost-Benefit Analysis 3. Basic Postulates 4. Limitations.

Meaning of Cost Benefit Analysis:

In general parlance, cost benefit analysis (CBA) refers to changes in the allocation of resources brought about by a project.

In this the investor looks at the allocation of resources before and after the installation of the project. Given some norm of calculating social welfare, the investor compares the social welfare in two situations. If the social welfare is higher after the installation of the project, then the project is worthwhile, otherwise it is not.

The term cost benefit analysis refers to the measurement of the net economic benefits from any change in resource allocation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the context of public finance, it means the calculation of net social benefits arising from a specific public expenditure such as a road, a bridge, an irrigation project or a disease prevention programme.

Cost-benefit analysis may also be applied to broader programmes of expenditures such as post-secondary education or research and development. In a sense, cost-benefit analysis seeks to describe and quantify the social advantages and disadvantages of investment in terms of a common monetary unit.

It is a fiscal instrument used by planners to evaluate the impact of the proper investment projects. It represents a practical technique for determining the relative merits of alternative government projects overtime.

The aim of cost benefit analysis is to channelize resource into projects which will yield the greatest gain in net benefit to society. Net benefit is the excess of total benefit over total cost.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The list of these cost and benefits include both real and pecuniary elements. The real benefits and costs again may be direct or indirect and tangible or intangible. Real benefits are derived by final consumers of a project.

Real costs consist of withdrawal from other uses. Pecuniary benefits and costs occur because of the changes in relative prices caused by the provision of public services. Such changes in prices offer gains to some individuals and cause losses to others. In the analysis of distributional consequences, this concept is important.

Basically there are three stages involved in cost-benefit analysis. They are:

(1) Enumeration of all costs and benefits of the proposed project.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(2) Evaluation of all costs and benefits.

(3) Discounting future net benefits.

Net social benefit in any period can be defined as the difference between total social benefits and total social costs which are measured both directly and indirectly. There are two efficiency criteria for guiding the selection among alternative investment projects.

They are benefiting cost ratio and the net benefit criterion. Benefit cost ratio relates to the present value of the total benefits which flow from a particular investment project to the present value of the total cost of the project. The net benefit criteria consist of the total benefit minus the total cost of the project.

Fundamentals of Cost-Benefit Analysis:

Cannons and theories of public expenditure generally set out certain norms governing the principles of government spending. Likewise control and accountability of public expenditure ensures that the proper limit to public expenditure is observed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However it will not help to fix any efficiency norm of public expenditure when a certain amount is spent by the state, certain expected results must flow from the project, benefiting the whole community.

This necessitate evolving a procedure which help the public authorities to locate areas of fruitful investment of public money. Hence in project assessment and evaluation cost-benefit analysis is an important tool devised in recent years.

Conceptually, cost-benefit analysis has been known to theoretical economists for more than one hundred and thirty years. The nineteenth century French Economist Jules Dupuit referred to the subject as early as 1844.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, the applicability of the theory of cost-benefit analysis appears to have been first tested in the USA not by economists but by engineers, in the 1930s. The US Flood Control Act of 1936 is considered to be the key document which set forth as standard in the evaluation of proposals for water resource development.

In 1950, another attempt was made to introduce uniformity into the standards and criteria used in the formulation and evaluation of the techniques of cost-benefit analysis. In the United Kingdom, the use of cost-benefit analysis came later where it has so far been used mainly in the field of transport.

Use of cost-benefit analysis in India started in the sixties, but on a limited scale. Dr. K.N. Raj’s appraisal of Bakra -Nangal project in North India was one of the first few systematic attempts in this field. The programme evaluation organization of the planning commission used cost benefit analysis in a number of case studies of major irrigation projects in early 1960’s.

However earlier efforts in the use of CBA were by way of ex-post facto evaluations. Recently the planning commission has been insisting upon cost benefit analysis as a criterion for “passing” a project for public investment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, cost- benefit analysis in the Indian context differs basically from its use in USA and UK. In India, the major economic decisions are centrally planned and taken by the government of India on the advice of planning commission.

More over rapid economic growth appears to be the main objective of government activity. Hence cost-benefit analyses have its application mainly for the projects which form part of the development programme undertaken by government.

Basic Postulates of Cost Benefit Analysis:

Cost benefit analysis is a complex matter. However it ideally guides an optimal allocation of resources between both the private and public sectors of the economy as well as within the public sector.

Many of the basic principles of cost benefit analysis are generally derived from welfare economics:

1. Allocative Efficiency or Appropriate Decision Rule:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To arrive at a measure of net benefits, formulation of a general decision rule, according to which the various benefits and costs might be aggregated, is imperative in cost-benefit analysis. This will enable us to discuss the problems of measurement of costs and benefits in cost benefit analysis.

Formulation of a decision rule provides a scientific basis for acceptance or rejection of a particular project. Projects yield a stream of benefits and costs that stretch over a period of time. Then the question arises what determines the allocative efficiently of the projects?

Allocation of resources to their best and most efficient uses is the underlying principle of cost benefit analysis. Efficiency in resource allocation is attained, when the total net benefit to the society from the project is maximized.

Total net benefit equal total benefit minus total cost. Projects are usually ranked according to the present value of their discounted net benefits or according to the ratio of the present value of benefits to the present value of costs. All projects with positive net benefits are considered for approval.

Similarly all projects with benefit cost ratios in excess of a value of one (1) are considered for approval. Use of these rules ensures that inefficient projects will not be considered for approval. In any given year in a society a certain level of service has already been provided.

It is difficult to determine whether this service is the efficient quantity. Consider for example, construction of additional new highway. In a given year a certain length of interstate highways are existing. The project proposal for new highway construction represent additional unit of service to the society.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this case the new highway construction will improve efficiency only if the marginal social benefit from the proposed new highway exceeds the marginal social cost from it. Figure No. 3.3 demonstrates the Allocative efficiency of the new highway construction project under consideration.

Marginal social benefits and marginal social cost of highway project available each year is measured in kilometers.

The length of highway currently existing is M1 kms. Suppose a new highway project is proposed, which may increase the road length to M2 kms. The proposed project will add an additional Δ M1 kms, of roads to available highways.

A cost benefit analysis of the project undertaken shows that Δ M1 kms of additional road length has a positive net benefit or a benefit cost ratio greater than one.

Technically it means that the area M1 AB M2, which represents marginal social benefit of the project, would exceed the area M1 DCM2, which represent, marginal social cost of the extra Kms of highway construction Approval of the project moves output close to the most efficient level M’ at which MSB : MSC.

Let us further assume that the existing length of highway is M3 Suppose there is a proposal to increase the highway length to M4.

In this case the increment in road length supplied through the new project ( Δ M2). Will be inefficient. This is so because, the marginal social cost of Δ M2 length of road, (M3 FG M4) exceeds the marginal social benefit from the same proposal (M3 KH M4). This is so because, M3 level of output is greater than the most efficient level of output at point M.

The analysis clearly shows that when net benefits are maximized resources are allocated efficiently. Even though this principle focuses on private market, the same principle applies to allocative efficiency in public markets.

2. Cost-Benefit Evaluation:

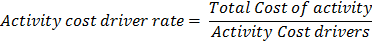

The evaluation of costs and benefits is the next major problem to be considered in project evaluation and selection. It involves measuring in monetary terms the benefits and costs in each period and in choosing the correct discount rate, at which to aggregate the time stream of benefits and costs.

In a perfect market, benefits can be calculated on the basis of the amount the users are willing to pay. But the problem of valuation is difficult, in the case of output of certain programmes, say for example, defence.

In order to overcome this difficulty, the use of shadow price is usually suggested. In a perfectly competitive market where all economic resources are fully employed, the money costs and revenues based on the market price measure the real costs or social costs and real benefits or social benefits of an investment.

The requirement for shadow pricing arises when market prices do not reflect social values. A general case of this occurs when a project uses an input purchased on a distorted market where the distortion takes the form of a divergence between the demand price and the marginal cost.

Thus shadow price are those valuations, other than the observed market prices, that are, so assigned, per unit of output or input that will be equal to its marginal social significance.

Use of the concept of opportunity cost has been suggested as a measure of shadow prices. These kinds of valuations replacing market prices in the cost-benefit analysis are generally termed as shadow prices. Thus we shall have shadow labour cost or shadow wages, shadow foreign exchange rate, shadow cost of capital etc. to reveal the valuation that society attaches to the inputs and outputs of the project.

An additional problem arises with inputs and outputs that are marketable, but whose prices do not reflect their true social value owing to monopolistic practices, subsidies taxes etc… Under such condition prices must be adjusted to reflect the actual marginal social cost or benefit.

3. Evaluation of Intangibles:

An investment project often involves intangible costs and benefits. The project evaluate must derive a monetary measure of these benefits and costs. For example, the major benefits of a transport renovation project are the save in precious time.

Suppose a road widening project reduces the running time of vehicles and enables the operators of vehicles to save their precious time, which they can utilize for some other activities prudently.

Here the opportunity cost of time saved is the amount of money that the beneficiaries of the saved time, will be willing to pay to have that time saving. Saved time can be used for doing other activities or to enjoy leisure. The project evaluator should develop different methods to evaluate the increase in these activities.

Projects sometimes evolve beneficial or harmful effects on the society. These usually take the form of external effects. Physical externalities are important items to be considered in project evaluation. For example, an irrigation project or the construction of a new airport involves a lot of external effects and creates impact on property values.

A good project evaluator is supposed to systematically catalogue the external effects and find out some method of estimating them.

4. Discounting Future Net Benefit:

The next step involved is to discount all future net benefits. After measuring the cost and benefits, the project evaluator, should develop an appropriate discount rate, to aggregate them to present value.

The need to discount steps from the existence of positive interest rates in the economy. Positive interest rates imply that a dollar of benefits in the future will be worth less than an equivalent dollar of present benefit. The interest rate Y called the social rate of discount is used to compute the present value.

The social discount rate is the rate at which society discounts a marginal addition to consumption in the future relative to the present. If the market interest rate net of tax is Y and it we assume capital market are perfect, individuals will arrange their time stream of consumption such that the marginal rate of substitution between the consumption of any two periods is 1/(1+r). The market rate ‘r’ is the private discount rate.

5. Choosing the Social Rate of Discount:

The social rate of discount should reflect the return that can be earned on resources employed in alternative private uses. This is the opportunity cost of funds invested by the government in a project.

Misallocation will not occur, if discount rate is set at par to the social opportunity cost of funds. For a private enterprise or public corporation, the discount rate is generally the rate of interest at which bank loans are available.

In case of enterprises using its own funds, it is the rate at which the bank would have paid for the deposits of such funds. In the case of public investments, the discount rate is set by the central planning authority. This rate is closely related to the concept of alternative use of funds.

Normally planners advocate using the rule of Net Present Value (NPV) in choosing investment projects. Present value is today’s value of dollar received in the future. Suppose if a person deposits $1000 today, he can earn $50 in one year, when the interest rate is 5 percent. The dollar value of this investment is therefore $1,050 receivable one year from today. This can be expressed as A1 = A0 + rA0 = A0(1+r)

Where A0 is the initial deposit, ‘r’ is the interest rate, and A. is the future value of the initial investment. From the above equation we can see that A1 = A0 + rA0 = ($1050) = ($1000) + 0.5 ($1000).

This principle insists that projects should be accepted or rejected depending on whether the net present value is positive or negative. If the net present value is positive or zero, the project may be chosen for implementation. If the net present value is negative, the project may be rejected.

Cost-benefit analysis provides a frame work for evaluating the usefulness of alternative public projects. If allows for comparison of alternative projects characterized by dissimilar distributions of cost and benefits over time. The fundamental rule of cost benefit analysis is to locate resources to their most efficient uses.

Present value analysis measures cost and benefits in terms of what future dollars are worth to us today. The rate of discount is the interest rate used to calculate present value. The three major methods for choosing between projects on the basis of the present value frame work are: maximum present value of net benefits, internal rate of discount and benefit cost ratios.

Problems associated with using internal rates of discount and benefit cost ratios indicate that maximum present value of net benefits is the best criterion for assigning priority to projects.

Limitations of Cost Benefit Analysis:

Cost benefit analysis is not easy to implement. A number of difficulties arise in the evaluation of projects and defining and measuring the concepts.

(a) Difficulties in Cost Benefit Assessment:

Benefits are both direct and indirect. In many cases, these are no private market counterparts from which to estimate benefit levels. Assessment of benefit is rendered difficult due to the presence of the element of uncertainty in a new project.

Uncertainty, relate to the risk involved in forecasting demand-supply of products and prices “flowing from the projects. The existence of external factors also poses a threat to scientific evaluation of project benefits.

(b) Difficulties in Cost Assessment:

Costs are difficult to estimate as well. There are problems in estimating costs in non-competitive markets.

There are external effects in non-competitive markets, which are difficult to quantify. Moreover in cost estimation opportunity cost is a widely used concept in project cost calculation. However in developing economics, market prices usually do not reflect the opportunity cost.

(c) Difficulties in Choosing the Appropriate Discount Rate:

Choosing the appropriate discount rate needs much care. The social rate of discount can always become arbitrary. There is no perfect method to find the most suitable social rate of discount for an investment project.

(d) Lacks Human Flexibility:

Prof. J. F. Due has asserted that cost-benefit analysis “is government by computer”. It lacks human flexibility. The project evaluation techniques are administered by technicians rather than by elected representatives of the people in a democratic society.

(e) Ignores the Income Redistribution Effects:

The cost benefit analysis focuses only on the allocational gains of resource deployment. It ignores the income redistribution effects of investment projects.

Prof. J. F. Due further observes that “the greatest specific usefulness is found at lower levels of the governmental decision making process, in selection among alternative means of accomplishing given ends and with activities such that quantification of benefit is possible on some reasonable basis”.