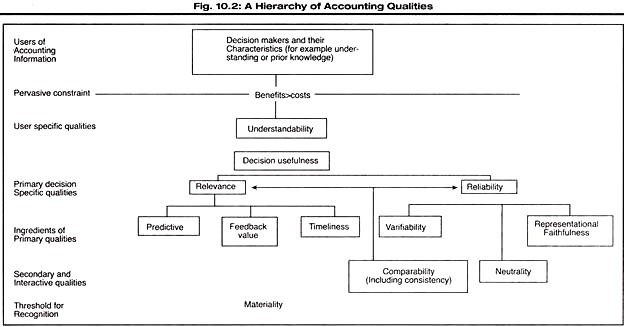

The following points highlight the top eleven characteristics of accounting information. The characteristics are: 1. Relevance 2. Reliability 3. Understandability 4. Comparability 5. Consistency 6. Neutrality 7. Materiality 8. Timeliness 9. Verifiability 10. Conservatism 11. Substance over Form.

Characteristic # 1. Relevance:

Relevance is closely and directly related to the concept of useful information. Relevance implies that all those items of information should be reported that may aid the users in making decisions and/or predictions. In general, information that is given greater weight in decision-making is more relevant.

Specially, it is information’s capacity to make a difference that identifies it as relevant to a decision. American Accounting Association’s Committee to Prepare A Statement of Basic Accounting Theory defines relevance as “the primary standard and requires that information must bear upon or be usefully associated with actions it is designed to facilitate or results desired to be produced”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Financial Accounting Standards Board in its Concept No. 1 comments:

“Relevant Accounting information must be capable of making a difference in a decision by helping users to form predictions about the outcomes of past, present and future events or to confirm or correct expectations.”

The question of relevance arises after identification and recognition of the purpose for which the information will be used. It means that information relevant for one purpose may not be necessarily relevant for other purposes. Information that is not relevant, is useless because that will not aid users in making decisions.

The relevant information also reduces decision-maker’s uncertainty about future acts. A necessary test of the relevance of reportable data is the ability to predict events of interest to statement users. To say that accounting information has predictive value is not to say that it is itself a prediction.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Predictive value here means value as an input into a predictive process, not value directly as a prediction. Users can be expected to favour those sources of information and analytical methods that have the greatest predictive value in achieving their specific objectives.

In today’s complex financial accounting environment, a general purpose report aims to fulfil the common needs of users so that information should be relevant to all users. In judging relevance of general purpose information, attention is focused on the common needs of users and specific needs of particular users will not be considered in this relevance judgement.

It is difficult to prepare a general purpose report which may provide optimal information for all possible users and which may command universal relevance. However, this has been recognised a potentially satisfactory solution.

To conclude, relevance is the dominant criterion in taking decisions regarding information disclosure. It follows that relevant information must be reported Relevance has been defined in accounting literature, but no satisfactory set of relevant items of information has been suggested. In this regard, an important task is to determine the needs of user(s) and the terms of information that are relevant to target user(s).

Characteristic # 2. Reliability:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Reliability is described as one, of the two primary qualities (relevance and reliability) that make accounting information useful for decision-making. Reliable information is required to form judgements about the earning potential and financial position of a business firm. Reliability differs from item to item.

Some items of information presented in an annual report may be more reliable than others. For example, information regarding plant and machinery may be less reliable than certain information about current assets because of differences in uncertainty of realisation. Reliability is that quality which permits users of data to depend upon it with confidence as representative of what it purports to represent.

FASB Concept No. 2 concludes:

The reliability of a measure rests on the faithfulness with which it represents what it purports to represent, coupled with an assurance for the user that it has that representational quality. To be useful, information must be reliable as well as relevant. Degrees of reliability must be recognised.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is hardly ever a question of black or white, but rather of more reliability or less. Reliability rests upon the extent to which the accounting description or measurement is verifiable and representationally faithful. Neutrality of information also interacts with those two components of reliability to affect the usefulness of the information.

FASB (USA) finds that it is not always easy to maintain a clear distinction between relevance and reliability, yet it is important to try to keep the two concepts apart. To explain this point, the FASB (Concept No. 2) illustrates further.

“Two different meanings of reliability can be distinguished and illustrated by considering what might be meant by describing a drug as reliable. It could mean that the drug can be relied on to cure or alleviate the condition for which it was prescribed, or it could mean that a dose of the drug can be relied on to conform to the formula shown on the label. The first meaning implies that the drug is effective at doing what it is expected to do. The second meaning implies nothing about effectiveness but does imply a correspondence between what is represented on the label and what is contained in the bottle.”

There are many factors affecting the reliability of information such as uncertainties inherent in the subject-matter and accounting measurements. Accounting measurements, like others, may be subject to error. A continuing source of misunderstanding about accounting information and measurements is the tendency to attribute to them a level of precision which is not practicable or attainable.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The possibility of error in measuring information and business events may create difficulty in attaining high degree of reliability. Thus, measurement constraints in accounting place restriction on the accuracy and reliability of information. Adequate disclosure in annual reports, however, requires that users should be informed about the data limitations and the magnitude of possible measurement errors.

The reliability concept does not imply 100 per cent reliability or accuracy. Non-disclosure of limitations attached with information will mislead the users. It can be noted that the most reliable information may not be the most significant for users in making economic decisions and assessment of an enterprise’s earning power.

It is the responsibility of management to report reliable information in annual reports. The goal of reliable information can be achieved by management if it applies generally accepted accounting principles, appropriate to the enterprise’s circumstances, maintains proper and effective systems of accounts and internal control and prepares adequate financial statements. If corporate management decides to disclose uncertainties and assumptions in annual reports, they will increase the value of the information expressed therein.

Relevance and Reliability:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Relevance and reliability are the two primary characteristics that make accounting information useful for decision-making. Ideally, financial reporting should produce information that is both more reliable and more relevant. In some situations, however, it may be necessary to sacrifice some of one quality for a gain in another. Reliability and relevance often impinge upon each other.

Reliability may suffer when an accounting method is changed to gain relevance, and vice versa. Sometimes it may not be clear whether there has been a loss or gain either of relevance or of reliability. The introduction of current cost accounting will illustrate the point.

Proponents of current cost accounting believe that current cost income from continuing operations is a more relevant measure of operating performance than is operating profit computed on the basis of historical costs.

They also believe that if holding gains and losses that may have accrued in past periods are separately displayed, current cost income from continuing operations better portrays operating performance. The uncertainties surrounding the determination of current costs, however, are considerable, and variations among estimates of their magnitude can be expected.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Because of those variations, verifiability or representational faithfulness components of reliability, might diminish. Whether there is a net gain to users of the information obviously depends on the relative weights attached to relevance and reliability (assuming, of course, that the claims made for current cost accounting are accepted).

It has also been argued that there is no conflict between relevance and reliability concepts when applied to financial accounting and reporting. For example, Stanga concludes in his study that financial accounting concepts of relevance and reliability are complementary rather than conflicting in nature. That is, increases in relevance tend to be associated with increases in reliability and vice versa.

The results of the study do not support that a substantial amount of one quality must necessarily be sacrificed or traded off in order to enhance the value of the other. Instead, both qualities may be enhanced simultaneously.

An implication is that accounting researchers and policy-makers should not be content with merely trying to improve the relevance of accounting disclosures. Resources must also be directed toward the development and perfection of methods designed to enhance the reliability of accounting measurements.

Characteristic # 3. Understandability:

Understandability is the quality of information that enables users to perceive its significance. The benefits of information may be increased by making it more understandable and hence useful to a wider circle of users. Presenting information which can be understood only by sophisticated users and not by others, creates a bias which is inconsistent with the standard of adequate disclosure.

Presentation of information should not only facilitate understanding but also avoid wrong interpretation of financial statements. Thus, understandable financial accounting information presents data that can be under-stood by users of the information and is expressed in a, form and with terminology adopted to the user’s range of understanding.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Corporate Report observes:

“Understandability does not necessarily mean simplicity, or that information must be presented in elementary terms, for that may not be consistent with the proper description of complex economic activities. It does mean that judgement needs to be applied in holding the balance between the need to ensure that all material matters are disclosed and the need to avoid confusing users by the provision of too much detail. Understandability calls for the provision, in the clearest form, of all the information which the reasonably instructed reader can make use of and the parallel presentation of the main features for the use of the less sophisticated.”

Understandability of information is governed by a combination of user characteristics, and characteristics inherent in the information. Understandability (and other qualifies of the information), should be determined in terms of broad classes of users (decision-makers) rather than particular user groups.

Since company financial reporting aims at general purpose external financial reporting, all relevant users’ needs should be considered in deciding the understandability of the information, and no decision should be based on specific circumstances of individual decision-makers. That is, accounting information should not be limited to the interests of the average investor or sophisticated users but, in fact, information should be ordered and arrayed to serve a broad range of users.

Characteristic # 4. Comparability:

Economic decision requires making choice among possible courses of actions. In making decisions, the decision-maker will make comparisons among alternatives, which is facilitated by financial information. Comparability implies to have like things reported in a similar fashion and unlike things reported differently.

Hendriksen observes that the “primary objective of comparability should be to facilitate the making of predictions and financial decisions by creditors, investors and others”. He defines comparability as “the quality or state of having enough like characteristics to make comparisons appropriate”.

FASB (USA) Concept No. 2 (pare 115, 1980) defines comparability, “….as the quality or state of having certain characteristics in common, and comparison is normally a quantitative assessment of the common characteristics. Clearly, valid comparison is possible only if the measurements used—the quantities or ratios— reliably represent the characteristic that is the subject of comparison”.

Comparable financial accounting information presents similarities and differences that arise from basic similarities and differences in the enterprise or enterprises and their transactions, and not merely from difference in financial accounting treatment.

Information, if comparable, will assist the decision-maker to determine relative financial strengths and weaknesses and prospects for the future, between two or more firms or between periods in a single firm.

Financial reports of different firms are not able to achieve comparability because of differences in business operations of companies and also because of the management’s viewpoints in respects of their transactions. Also, because there are different accounting practices to describe basically similar activities.

Two corporate managements may view the similar risk, uncertainty, benefit or sacrifice in different fashions and, thus, this would lead to different implications of financial statements. With information that facilitates interpretation, users are able to compare and assess the results of similar transactions and other events among enterprises.

Efforts, therefore, should be directed towards developing accounting standards to be applied in appropriate circumstances to facilitate comparisons and interpretation of data: areas of differences in accounting practices, which are not justified by differences in circumstances, should be narrowed; selection of an accounting practice should be based on the economic substance of an event or a transaction being measured and reported; and a desire to produce a particular financial statement result should not influence choice between accounting alternatives.

Characteristic # 5. Consistency:

Consistency of method over a period of time is a valuable quality that makes accounting numbers more useful. Consistent use of accounting principles from one accounting period to another enhances the utility of financial statements to users by facilitating analysis and understanding of comparative accounting data.

It is relatively unimportant to the investor what precise rules or conventions are adopted by a company in reporting its earnings, if he knows what method is being followed and is assured that it is followed consistently from year to year.

Lack of consistency produces lack of comparability. The value of inter-company comparisons is substantially reduced when material differences in income are caused by variations in accounting practices.

The quality of consistency can be applied in different situations, e.g., use of same accounting procedures by a single firm or accounting entity from period to period, the use of similar measurement concepts and procedures for related items within the statement of a firm for a single period, and the use of same procedures by different firms.

If a change in accounting practices or procedures is made, disclosure of the change and its effects permits some comparability, although users can rarely make adjustments that make the data completely comparable.

Consistency in the use of accounting procedures over a period is a user constraint, otherwise there would be difficulty in making predictions. If different measurement procedures are adopted, it is difficult to predict trends in earning power or financial position of a company.

If assets are valued at cost in some periods, and at replacement cost in others, the firm’s earning power may be distorted, especially when the difference in cost and replacement cost is significant over a period of time.

Although consistency in the use of accounting principles from one accounting period to another is a desirable quality, but it, if pushed too far, will prove a bottleneck for bringing about improvements in accounting policies, practices, and procedures. No change to a preferred accounting method can be made without sacrificing consistency; there is no way that accounting can develop without change.

Users’ needs may change over time which would require a change in accounting principles, standards and methods. These improvements are needed to serve users’ needs in changing circumstances. When it is found that current practices or presentations being followed are not fulfilling users’ purposes, a new practice or procedure should be adopted.

According to Backer, “different accounting methods are needed to reflect different management objectives and circumstances. The consensus of opinion among analysts interviewed was that standards are desirable as guidelines to financial reporting, but that management should be free to depart from these standards provided methods used and their effects are clearly disclosed”. Thus, consistency and uniformity in accounting methods would not necessarily bring comparability.

Instead of enforced uniformity, accounting standards should be developed which would be best or preferred methods in most cases. Such accounting standards should be followed unless there is a compelling reason why they will not provide a correct and useful reflection of business operations and results.

Also, full disclosure should be made of the alternative method applied and, whenever practical, of the monetary difference resulting from deviations from the standard. To conclude, consistency is desirable, until a need arises to improve practices, policies, and procedures.

Characteristic # 6. Neutrality:

Neutrality is also known as the quality of ‘freedom from bias’ or objectivity. Neutrality means that, in formulating or implementing standards, the primary concern should be the relevance and reliability of the information that results, not the effect that the new rule may have on a particular interest or user(s).

A neutral choice between accounting alternatives is free from bias towards a predetermined result. The objectives of (general purpose) financial reporting serve many different information users who have diverse interests, and no one predetermined result is likely to suit all users’ interests and purposes.

Therefore, accounting facts and accounting practices should be impartially determined and reported with no objective of purposeful bias toward any user or user group. If there is no bias in selection of accounting information reported, it cannot be said to favour one set of interests over another. It may, in fact, favour certain interests, but only because the information points that way.

To say that information should be free from bias is not to say that standards setters or providers of information should not have a purpose in mind for financial reporting. In fact, information must be purposeful. Neutrality neither means ‘without purpose’ nor does it mean that accounting should be without influence on human behaviour.

Accounting information cannot avoid affecting behaviour, nor should it. If it were otherwise, the information would be valueless—by definition, irrelevant and—the effort to produce it would be futile.

It is, above all, the predetermination of a desired result, and the consequential selection of information to induce that result, that is the negation of neutrality in accounting. To be neutral, accounting information must report economic activity as faithfully as possible, without colouring the image it communicates for the purpose of influencing behaviour in some particular direction.

For a standard to be neutral, it is not necessary that it treats everyone alike in all respects. A standard could require less disclosure from a small enterprise than it does from a large one without having its neutrality impugned. Nevertheless, in general, standards that apply differently need to be looked at carefully to ensure that the criterion of neutrality is not being violated.

Characteristic # 7. Materiality:

The concept of materiality permeates the entire field of accounting and auditing. The materiality concept implies that not all financial information need or should be communicated in accounting reports—only material information should be reported.

Immaterial information may and probably should be omitted. Information should be disclosed in the annual report which is likely to influence economic decisions of the users. Information that meets this requirement is material.

In recent accounting literature, where relevance and reliability are held upon as the primary qualitative characteristics that accounting information must have if it is to be useful, materiality is not recognised as a primary characteristic of the same kind. Materiality judgments are, primarily, quantitative in nature.

They are described as the relative quantitative importance of some piece of financial information to a user, in the context of a decision to be made. They pose the question: Is this item large enough for users of information to be influenced by it?

However, the answer to that question will usually be affected by the nature of the item; items too small to be thought material, if they result from routine transactions, may be considered material if they arise in abnormal circumstances. Thus, materiality of an item depends not only upon its relative size, but also upon its nature or combination of both, that is, on either quantitative or qualitative characteristics, or on both.

Generally, the decision-makers (investor, accountant and manager) see materiality in relation to actual assets or income. Investors see materiality in terms of the rate of change or change in the rate of change. What seems not to be material in business may turn out to be very important in the investment market. It has been established that the effect on earnings was the primary standard to evaluate materiality in a specific case.

Guidelines to test materiality are amount of the item, trend of net income, average net income for a series of years, assets, liabilities, trends and ratios that establish meaningful analytical relationship of information contained in annual reports. Almost always, the relative rather than the absolute size of a judgment item determines whether it should be considered material in a given situation.

Losses from bad debts or pilferage that could be shrugged off as routine by a large business may threaten the continued existence of a small one. An error in inventory valuation may be material in a small enterprise for which it cut earnings in half, but immaterial in an enterprise for which it might make barely perceptible ripple in the earnings.

Another factor in materiality judgments is the degree of precision that is attainable in estimating the judgment item. The amount of deviation that is considered immaterial may increase as the attainable degree of precision decreases. For example, accounts payable usually can be estimated more accurately than can contingent liabilities arising from litigation or threats of it, and a deviation considered to be material in the first case may be quite trivial in the second.

Relevance and Materiality:

Materiality, like relevance, is not usually considered by accountants as a qualitative characteristic. Materiality is directly related to measurement and is a quantitative characteristic. Materiality judgements have been partially based on an item of information’s relative size when compared with some pertinent base such as net income or revenue.

Of course, in some situations, the nature of some items of information may dictate their materiality regardless of their relative size or the fact that they cannot be adequately quantified. Magnitude of the item by itself, without regard to the nature of the item and the circumstances in which the judgment has to be made, will not generally be a sufficient basis for a materiality judgment.

Relevance generally refers to the nature of the item with respect to specific or general uses of financial reports, while materiality refers to the significance of a specific item in a specific context. In spite of the differences in the two concepts (relevance and materiality) both have much in common—both are defined in terms of what influences or makes a difference to an investor or other decision-maker.

Characteristic # 8. Timeliness:

Timeliness means having information available to decision-makers before it loses its capacity to influence decisions. Timeliness is an ancillary aspect of relevance. If information is either not available when it is needed or becomes available long after the reported events that it has no value for future action, it lacks relevance and is of little or no use. Timeliness alone cannot make information relevant, but a lack of timeliness can rob information of relevance it might otherwise have had.

Clearly, there are degrees of timeliness. Some reports need to be prepared quickly, say in case of takeover bid or strike. In some other contexts, such as routine reports by a business firm of its annual results, a longer delay in reporting information may materially affect the relevance and, therefore, the usefulness of information. But in order to have gain in relevance that comes with increased timeliness, it may involve sacrifices of other desirable characteristics of information, and as a result there may be an overall gain or loss in usefulness.

For example, it may sometimes be desirable to sacrifice precision for timeliness, for an approximation produced quickly is often more useful than precise information that is reported after a longer delay. It can be argued that if in the interest of timeliness, the reliability of the information is sacrificed to a material degree, the usefulness of the information may be adversely affected.

While every loss of reliability diminishes the usefulness of information, it will often be possible to approximate an accounting number to make it available more quickly without making it materially unreliable. As a result, its overall usefulness may be enhanced.

Characteristic # 9. Verifiability:

The quality of verifiability contributes to the usefulness of accounting information because the purpose of verification is to provide a significant degree of assurance that accounting measures represent, what they purport to represent. Verification does not guarantee the suitability of method used, much less the correctness of the resulting measure.

It does convey some assurance that the measurement rule used, whatever it was, was applied carefully and without personal bias on the part of the measurer. In this process, verification implies and enhances consensus about measurements of some particular phenomenon.

The Accounting Principles Board of USA defines verifiability as:

“Verifiable financial accounting information provides results that would be substantially duplicated by independent measurers using the same measurement methods.”

According to FASB, “Verifiability means no more than that several measurers are likely to obtain the same measure. It is primarily a means to attempting to cope with measurement problems stemming from the uncertainty that surrounds accounting measures and is more successful in coping with some measurement problems than others. Verification of accounting information does not guarantee that the information has a high degree of representational faithfulness and a measure with a high degree of verifiability is not necessarily relevant to the decision for which it is intended to be useful.”

Characteristic # 10. Conservatism:

Conservatism is generally referred to as a convention that many accountants believe to be appropriate in making accounting decisions.

According to APB (USA) Statement 4:

“Frequently, assets and liabilities are measured in a context of significant uncertainties. Historically, managers, investors, and accountants have generally preferred that possible errors in measurement be in the direction of understatement rather than overstatement of net income and net assets. This has led to the convention of conservatism.”

There is a place for a convention, such as conservatism—meaning prudence, in financial accounting and reporting, because business and economic activities are surrounded by uncertainty, but it needs to be applied with care. Conservatism in financial reporting should no longer connote deliberate, consistent, understatement of net assets and profits.

Conservatism is a prudent reaction to uncertainty to try to ensure that uncertainties and risks inherent in business situations arc adequately considered. Thus, if two estimates of amounts to be received or paid in the future are about equally likely, conservatism dictates using the less optimistic estimates.

However, if two amounts are not equally likely, conservatism does not necessarily dictate using the more pessimistic amount rather than the more likely one. Conservatism no longer requires deferring recognition of income beyond the time that adequate evidence of its existence becomes available, or justifies recognising losses before there is adequate evidence that they have been incurred.

Characteristic # 11. Substance over Form (Economic Realism):

Economic realism is not usually mentioned as a qualitative criterion in accounting literature, but it is important to investors. It is a concept, that seems easy to understand but hard to define because perceptions of reality differ. In essence, economic reality means an accurate measurement, of the business operations, that is, economic costs and benefits generated in business activity.

The definitional problem arises from cash vs., accrual accounting, or the principle of matching costs with revenues. Accrual accounting is necessary for complex organisations, of course, but, where accruals and estimates have a considerable degree of uncertainty as to amount or timing, cash accounting would seem to come closer to economic realism.

There have been tendencies in accounting for “the media to become the message”, i.e., for accounting numbers to become the reality rather than the underlying facts they represent. These tendencies appear through devices to smooth income such as too early recognition of income, deferral of expenses, and use of reserves.

These may give the illusion of steady earnings and as a result, both investors and management may feel better, but, in fact, there is a considerable fluctuation in business activity. Investors need to know the facts about these fluctuations; if they find it useful to average earnings, they can do so themselves. The objective should be “to tell it like it is.”

Evaluating the Qualitative Characteristics:

The above mentioned characteristics (relevance, materiality, understandability, comparability, consistency, reliability, neutrality, timeliness, economic realism) make financial reporting information useful to users. These normative qualities of information are based largely upon the common needs of users.

However, there are three constraints on full achievement of the qualitative characteristics:

(i) Conflict of objectives,

(ii) Environmental influences, and

(iii) Lack of complete understanding of the objectives.

The pursuit of one characteristic may work against the other characteristics. It is difficult to design financial reports which may be relevant to user needs on the one hand and also free from bias towards any particular user group on the other. The qualitative characteristics should be arranged in terms of their relative importance.

Desirable trade-offs among them should be determined. Some environmental factors such as difficulty in measuring business events, limitations of available data, users’ diverse requirements, affect accounting and thus put constraint on achieving objectives. Constraints also arise because users have different level of competence to handle large masses of data or to interpret summarised data in making predictions.

Many attempts have been made to examine the relative significance of (or possible conflict among) these qualitative characteristics. As stated earlier FASB Concept No. 2 (Qualitative Characteristics of Accounting Information May 1980) recognises relevance and reliability as primary qualitative characteristics and other remaining characteristics as ingredients of these primary qualities.

The American Accounting Association’s Committee on Statement of Accounting Theory and Theory Acceptance concludes:

“To be useful in making decisions, financial information must possess severe normative qualities. The primary one is the relevance to the particular decision at hand of the attribute selected for measurement. The secondary one is the reliability of the measurement of the (relevant) attribute. Objectivity, verifiability freedom from bias, and accuracy are terms for overlapping parts of the reliability quality. Other qualities, such as comparability, understandability, timeliness, and economy, are also emphasised. A set of such desirable qualities is used as criteria for evaluating alternative accounting methods.”

However, in another study conducted by FASB (USA) to know the participants’ views about the importance of the qualitative characteristics of financial statement data, the following ranking were obtained.

Reliability is considered the most important qualitative characteristic of financial statement data, comparability is considered second in importance, and uniformity is third. Timeliness is ranked sixth, ‘economic value assessment’ eight, and conservatism ninth. Perhaps the most surprising finding is the relatively low ranking to characteristics that economic theory would suggest are particularly meaningful if financial statements are used for investment decision-making.

Interestingly, economic value assessment is ranked ninth by the direct placement officers (investment officers)…… The analyses show that as investment officers gain more experience they tend to consider ‘economic value assessment’ less important, and timeliness and understandability more important, ceteris paribus.

A study conducted by Vickrey finds that FASB’s approach to the development of NIQs (Normative Information Qualities) seems to be based more on a working knowledge of decision-making in the empirical setting and intuition than on a rigorous economic analysis.

Vickrey has identified the following normative information quantities: signal relevance, cost effectiveness, act selectivity, state-predictive ability, reliability, representational faithfulness, timeliness, and understandability.

Finally, it can be concluded that there are likely to be trade-offs between qualitative characteristics in many circumstances. In a particular situation, the importance attached to one quality in relation to the importance of other qualities of accounting information will be different for different informatics users, and their willingness to trade one quality for another will also differ.

This quite significant as it makes the question of prefer-ability difficult and puts unanimity about preferences among accounting alternatives out of reach Although there is a considerable agreement about qualitative characteristics that accounting information should possess, no consensus is found about their relative importance in a specific situation because different users have or perceive themselves to have different needs, and therefore, have different preferences.

It has been suggested, that, “to be useful, financial information must have each of the qualities (mentioned) to a minimum degree. Beyond that, the rate at which one quality can be sacrificed in return for a gain in another quality without making the information less useful overall will be different in different situations.”