A footnote to the financial statements of Gerber Products Company disclosed a transaction carried out by one of the organization’s subsidiaries- “The Company’s wholly owned Mexican subsidiary sold previously unissued shares of common stock to Grapo Coral, S.A., a Mexican food company, at a price in excess of the shares’ net book value.” The footnote added that Gerber had increased consolidated Additional Paid-in Capital by $432,000 as a result of this stock sale.

As this illustration shows, subsidiary stock transactions can alter the level of parent ownership. A subsidiary, for example, can decide to sell previously unissued stock to raise needed capital. Although the parent company can acquire a portion or even all of these new shares, such issues frequently are marketed entirely to outsiders. A subsidiary could also be legally forced to sell additional shares of its stock.

As an example, companies holding control over foreign subsidiaries occasionally encounter this problem because of laws in the individual localities. Regulations requiring a certain percentage of local ownership as a prerequisite for operating within a country can mandate issuance of new shares. Of course, changes in the level of parent ownership do not result solely from stock sales: A subsidiary also can repurchase its own stock. The acquisition, as well as the possible retirement, of such treasury shares serves as a means of reducing the percentage of outside ownership.

Changes in Subsidiary Book Value—Stock Transactions:

When a subsidiary subsequently buys or sells its own stock, a nonoperational increase or decrease occurs in the company’s fair and book value. Because the transaction need not involve the parent, the parent’s investment account does not automatically reflect the effect of this change.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, a separate adjustment must be recorded to maintain reciprocity between the subsidiary’s stockholders’ equity accounts and the parent s investment balance. The accountant measures the impact the stock transaction has on the parent to ensure that this effect is appropriately recorded within the consolidation process.

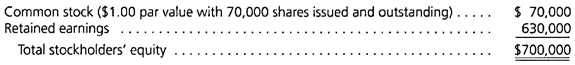

An example demonstrates the mechanics of this issue. Assume that on January 1, 2009, Small Company’s book value is $700,000 as follows:

Based on the 70,000 outstanding shares, Small’s book value at this time is $10 per common share ($700,000/70,000 shares).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

On this same date, Giant Company acquired in the open market an 80 percent interest in Small Company (56,000 of the outstanding shares). To avoid unnecessary complications, we assume that the fair value of this stock is $560,000, or $10 per share (for both the controlling and non-controlling interests), exactly equivalent to the book value of the shares. We also assume that this acquisition involves no goodwill or other revaluations.

Under these conditions, the consolidation process is uncomplicated. On the purchase date, only a single worksheet entry is required.

The investment account is eliminated and the 20 percent non-controlling interest recognized through the following routine entry:

We now introduce a subsidiary stock transaction to demonstrate the effect created on the consolidation process. Assume that on January 2, 2009, Small sells 10,000 previously unissued shares of its common stock to outside parties for $16 per share. Because of this transaction, Giant no longer possesses an 80 percent interest in a subsidiary having a $700,000 net book value.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Instead the parent now holds 70 percent (56,000 shares of a total of 80,000) of a company with a book value of $860,000 ($700,000 previous book value plus $160,000 capital generated by the sale of additional shares). Independent of any action by the parent company, the book value equivalency of this investment has risen from $560,000 to $602,000 (70 percent of $860,000). Small’s ability to sell shares of stock at $6 more than the book value has created this increase.

Small’s new stock issuance has increased the underlying book value component of Giant’s investment by $42,000 ($602,000 – $560,000). Thus, even with the rise in outside ownership, the business combination has grown in size by this amount, a change that the consolidated financial figures must reflect. As the Gerber example indicates, this adjustment is recorded to Additional Paid-in Capital. Because the subsidiary’s stockholders’ equity is eliminated on the worksheet, the parent must recognize any equity increase accruing to the business combination.

Therefore, the $42,000 increment is entered into Giant’s financial records as an adjustment in both the investment account (because the underlying book value of the subsidiary has increased) and Additional Paid-in Capital:

After the change in the parent’s records has been made, the consolidation process can proceed in a normal fashion. If, for example, the financial statements are brought together immediately following the sale of these additional shares, the following worksheet Entry S can be constructed. Although the investment and subsidiary equity accounts are removed here, the change recorded earlier in Giant’s Additional Paid-in Capital remains within the consolidated figures.

Thus, the subsidiary’s issuance of stock at more than the book value has increased the reported equity of the business combination:

Consistent with this view, this textbook treats the effects from subsidiary stock transactions on the consolidated entity as adjustments to Additional Paid-in Capital.

Subsidiary Stock Transactions—Illustrated:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

No single example can demonstrate the many possible variations that different types of subsidiary stock transactions could create. To provide a working knowledge of this process, we analyze several additional cases briefly.

The original balances presented for Small (the 80 percent- owned subsidiary) and Giant (the parent) at the beginning of the current year serve as the basis for these illustrations:

View each of the following cases as an independent situation. Also, all adjustments are made here to Additional Paid-in Capital.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Assume that Small Company sells 10,000 shares of previously unissued common stock to outside parties for $8 per share.

Small is issuing its stock here at a price below the company’s current book value of $10 per share. Selling shares to outsiders at a discount necessitates a drop in the recorded value of consolidated Additional Paid-in Capital. The parent’s ownership interest is being diluted, thus creating a decrease in the underlying book value of the parent’s investment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This reduction can be measured as follows:

In the original illustration, the subsidiary sold new shares at $6 more than book value, thus increasing consolidated equity.

Here the Opposite Transpires:

It issues the shares at a price less than book value, creating a decrease:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Assume that Small issues 10,000 new shares of common stock for $16 per share. Of this total, Giant acquires 8,000 shares to maintain its 80 percent level of ownership. Giant pays a total of $128,000 (8,000 × $16) for this additional stock. Outside parties bought the remaining shares.

Under these circumstances, the stock transaction alters both the parent’s investment account and the book value of the subsidiary.

Thus, both figures must be updated prior to determining the necessity of an equity revaluation:

This case requires no adjustment because Giant’s underlying interest remains properly aligned with the subsidiary’s book value. Any purchase of new stock by the parent in the same ratio as previous ownership does not affect consolidated Additional Paid-in Capital. The transaction creates no proportionate increase or decrease.

Assume that instead of issuing new stock, Small reacquires 10,000 shares from outside owners. It pays $16 per share for this treasury stock.

This illustration presents another type of subsidiary stock transaction- the acquisition of treasury stock. Although the subsidiary’s actions have changed, the basic accounting procedures are unaffected.

The subsidiary paid an amount in excess of the treasury stock’s $10 per share book value. Consequently, this also dilutes the parent’s interest. A transaction between the subsidiary and the noncontrolling interest created this effect; the reduction does not result from a purchase made by the parent. As in Case 1, the parent must report the change as an adjustment in its Additional Paid-in Capital accompanied by a corresponding decrease in its investment account (to $504,000 in this case).

Again, for reporting purposes, this transaction results in lowering consolidated Additional Paid-in Capital:

This fourth illustration represents a different subsidiary stock transaction, the purchase of treasury stock. Therefore, display of consolidation Entry S should also be presented.

This entry demonstrates the worksheet elimination required when the subsidiary holds treasury shares:

Assume that Small issues a 10 percent stock dividend (7,000 new shares) to its owners when the stock’s fair value is $16 per share.

This final case illustrates that not all subsidiary stock transactions produce discernible effects on the consolidation process. A stock dividend, whether large or small, capitalizes a portion of the issuing company’s retained earnings and, thus, does not alter book value. Shareholders recognize the receipt of a stock dividend only as a change in the recorded cost of each share rather than as any type of adjustment in the investment balance.

Because neither party perceives a net effect, the consolidation process proceeds in a routine fashion. Therefore, a subsidiary stock dividend requires no special treatment prior to development of a worksheet.

The consolidation Entry S made just after the issuance of this stock dividend follows. The $560,000 component of the investment account continues to be offset against the stockholders’ equity of the subsidiary.

Although the dividend did not affect the parent’s investment, the equity accounts of the subsidiary have been realigned in recognition of the $112,000 stock dividend (7,000 shares of $1 par value stock valued at $16 per share):